The Indian Film Renaissance or the Parallel Film Movement in India was a time that marked a period in Indian filmmaking that sought to unshackle itself from the meager tropes of Indian filmmaking.

Before the film renaissance, the concept of motion pictures was mostly limited to the primordial pride and respect for their country, and nationalism was heralded as a necessity. The entirety of the country was stuck in a stupor of being an independent democracy and a country newly freed from the bonds of colonialism.

The infinitesimal yet grand world of cinema post-independence was one where Indians were engulfed with a feeling of pride and an ethereal feeling of duty towards the nation.

Motion pictures based on saints and the state of the country had reached their zenith of production. The clause of movies had become to either educate or entertain, and the midpoint was never reached.

In the Indian film industry’s initial days, ‘Bollywood’ had not been formed yet. On the contrary, the Indian film industry was divided into regional film industries. Thus, the upheavals in revolutionizing cinema happened according to the language, rather than encapsulating the film industry as a whole.

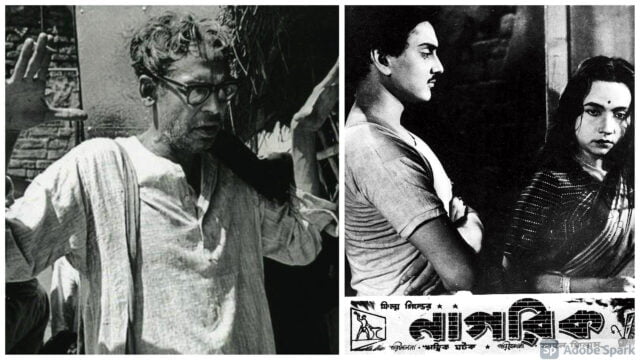

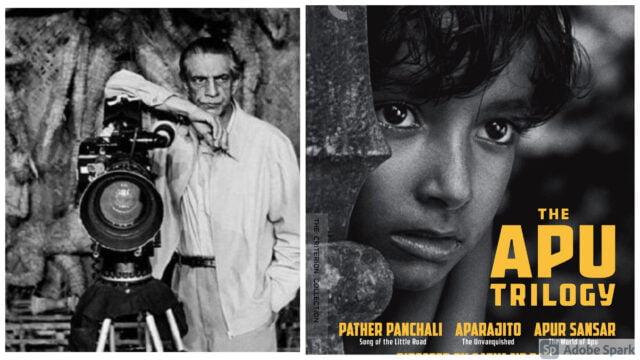

Thus, it is often said that Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali,’ bolstered the Indian New Wave movement and spearheaded the Bengali Film Renaissance. On the other hand, it is often touted as Ritwik Ghatak’s accomplishment as the shooting of Nagarik concluded in 1952 but was not released until 1977.

A lot many stories await as we venture into the deep depths of the Indian Film Renaissance and its efficacies.

What Was The Indian Film Renaissance Or The Indian New Wave?

The Indian New Wave was marked with the incessant production of movies that were grounded, tackled the usual gruff of India’s socio-political realities, and made do without the usual song and dance sequences.

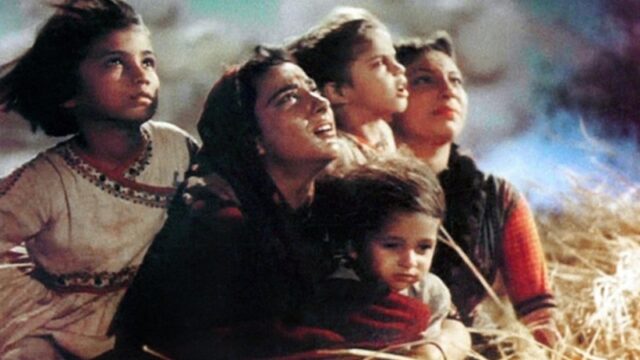

Originally referred to as the Indian Parallel Cinema movement, the cinematic movement began in the late 1940s with the release of Dharti Ke Lal (1946) and Neecha Nagar (1946). Both the movies were deemed exemplary in their own right, however, both of them were prerequisites to an era of technically sound and revolutionary movies to follow.

Neecha Nagar had been an amazing reference point for filmmakers during the infancy of the movement. The movie had gone on to define an era of succeeding auteurs thus marking the Golden Age of cinema.

The Indian New Wave found a lease of life with the release of Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, the first movie of the Apu Trilogy, that would go on to be declared a timeless classic. Ray’s cinematography, apart from being grounded, was based on modern sensibilities that were rooted in the base reflection of a person.

Thus, with the beginning of the Apu Trilogy, a fundamentally awesome form of filmmaking emerged from the usual mainstream extravagance of Indian cinema.

Gone were the days of grandiose musicals with the perfunctory by the numbers formula. An era of realism and socio-political commentaries had thus reared its head that sought to educate and entertain.

The Early Years Of The Parallel Cinema Movement

The Indian Film Renaissance had unofficially begun with Ritwik Ghatak’s Nagarik, a movie about the normal citizens grappling with the uncertainties of urban life.

However, owing to certain difficulties with having his film produced and a dearth of funds, it did not see the light of day until 1977. Ghatak, in his lifetime, had directed only eight movies, each one tanking a bit harder than the last and with each movie, he plunged further into chronic alcoholism.

Thus, with Ghatak’s initial magnum opus not finding any form of takers in the film industry, Satyajit Ray emerged as India’s finest auteurs with Pather Panchali. The diction of these years was markedly different from the socio-realistic portrayals of life as portrayed in Neecha Nagar.

Ray’s tales were of stoicism as much as they were of the reality of the society at the time, and they were much more a depiction of the human being than they were of the society. More often than not, the viewer would see society through the lenses of the protagonist themselves.

Also Read: Watch: Satyajit Ray’s Movies That Were Globally Watched And Appreciated

The titular character was thus alleviated into a vessel as well as another character. The entirety of the Apu Trilogy was a product of such filmmaking tendencies yet the camera never stopped to sympathize with the characters.

It empathized and watched the world through the understanding and lenses of Apu, from his early years to his adulthood. Human stories had received a different undertone from Ray.

It would be unfair to term Ray to be the first auteur to depict the humdrum social realities on screen, as Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin(1953) did it before Ray came to the scene. Do Bigha Zamin, much like Ray’s Apur Panchali, opened to amazing reviews and international recognition.

However, Ray’s mark was felt owing to the expectations and grounds he sought to create and break with each scene in Pather Panchali.

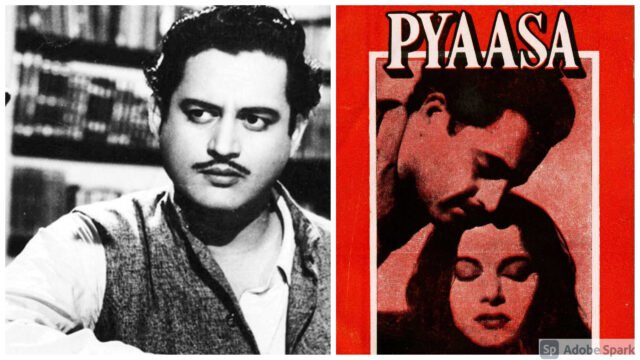

A similar portrayal of the world through the eyes of the titular character was perceived in the Guru Dutt directed Pyaasa, however, it sought to please the mainstream audiences as well. Some seek to refer to Pyaasa as a beautiful tragedy that breaks your heart no matter how many times you watch it. “A man is valued only after his death,” was the turgid idea that Dutt sought to portray on screen.

The movie was, in all certainty, the first attempt by any director to formulate the tragedies of a life of depravity and inequality through songs. The music and lyrical genius depicted in the movie also worked as a unique narrative tool.

The ball of imaginative yet grounded realities had started rolling and the film industry looked stronger than ever, as they proved that a movie with the most minimal budget was possible.

Directors Find A Middle Ground For Parallel Cinema

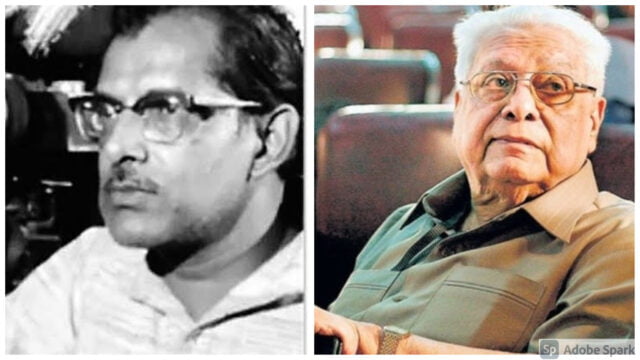

With the emergence of directors like Basu Chatterjee and Hrishikesh Mukherjee into the film industry, parallel cinema evolved into the mainstream as they created movies with a similar portrayal of ground realities but with the oomph of mainstream cinema.

The days of portraying ground realities in somber tones and realistic dramatizations were done away with as they portrayed the theatrics of the mainstream. Mukherjee’s Anand still stands as an amazing piece of cinema even after nearly fifty years.

His depiction and eventual answers to the mortal question of life and death still stand immortalized through the movie.

In the same vein, Basu Chatterjee’s depictions of Indian society finds a common ground in the way of the similar theatrics of the mainstream that mould themselves with the ground realities. His remake of 12 Angry Men, Ek Ruka Hua Faisla, still remains as one of the best depictions of jury politics and societal divisions from an Indian standpoint.

The Swan Song Of The Parallel Cinema Climate

As the 1980s came knocking, the people had reared their head towards grand depictions of violence and common citizens knocking down authority figures and the meager budget of parallel cinema could sparsely keep up.

Indira Gandhi’s emergency years had provided the people and the directors with the impetus for characters that emerged from the ashes of their society.

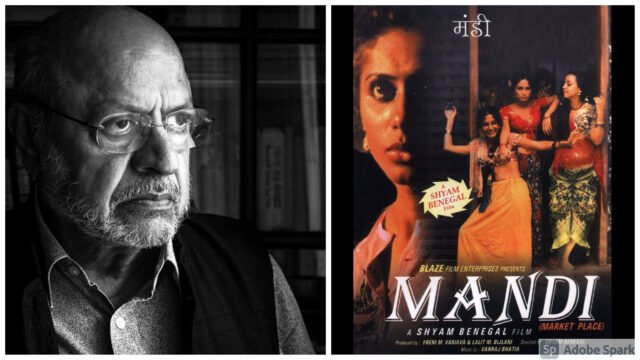

The era of the angry young man had begun, however, directors such as Shyam Benegal and Gulzar, amongst other renowned directors, still found major successes in their ventures.

Hindi cinema had found its grounds in the Indian Film Renaissance and the new breed of filmmakers had begun to follow the grounds laid down by the likes of Hrishikesh Mukherjee. Thus, they went on to make movies portraying ground realities with a similar sense of dramatization.

The dramatization was more often than not controlled to a certain degree to encapsulate the realities of the time while bringing their own individuality to the screen. Benegal’s Mandi stands as the perfect depiction of ground reality with a tinge of controlled dramatization. The masses still had people to project their qualms through cinema up until then.

With another generation of cinema rearing its head, the people were fed with loud, masala potboilers, as the film federation wanted movies to be limited to their entertainment value. The citizens had lost their mouthpiece and they were unaware of it.

However, as things stand, the generation of the film industry we are being raised in depicts cinema as a form of art that provides a voice to the mute and power to the weak.

They will not be dumbed down by the solitary projects of entertainment but they will know their surroundings. No matter what they say, a filmmaker does have the power to make and break a society. That is a fact.

Image Source: Google Images

Sources: Outlook, The Indian Express, University Of Texas at Austin, Huffington Post

Connect with the blogger: @kushan257

This post is tagged under: cinema movie, cinema video, hindi cinema, jio cinema, cinema news, cinema songs, bangla cinema, bangla cinema bangla cinema, cinema hall, satyajit ray, parallel cinema, apu trilogy, pather panchali, shyam benegal, mandi, ritwik ghatak, nagarik, ajantrik, gulzar, auteur, auteur cinema, films, theatre, Bollywood, movies, regional cinema, drama, amitabh bacchan, hrishikesh Mukherjee, anand, basu Chatterjee, over the top cinema, Netflix, amazon prime video, youtube, shemaroo.

Other Recommendations:

ResearchED: The Emergence Of Sugar Baby-Sugar Daddy Culture In India