By Prerna Bhatia

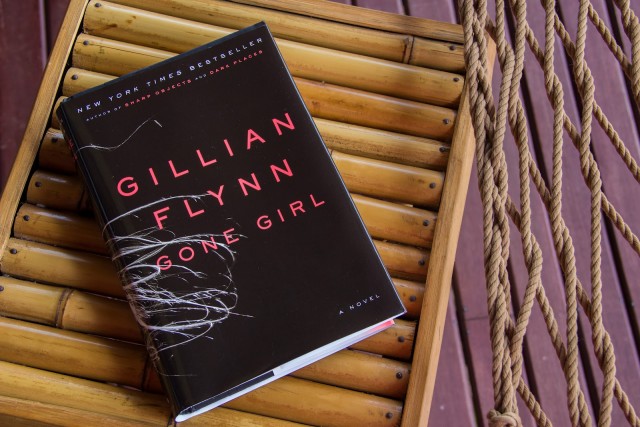

“What are you thinking? How are you feeling? What have we done to each other?”

These words echo in my mind every time I think about Gone Girl. And it was at the end of the book that I realised how much these words mattered.

I came across the synopsis of the book in the Sunday special of a daily. It instantly caught my attention, and I moved from reluctant admiration to ardent love for Gillian Flynn and went on to read her other works, Dark Places and Sharp Objects.

Gone Girl explores the toxic marriage between Nick and Amy. It is about wanting, and what happens when you want the wrong things, or when you get the wrong things you want. Most of all, it is about losing your identity while wanting to be the best for your spouse. This is where Amy’s problems start.

Gillian Flynn explains Amy’s situation in the beautiful, and perhaps, the most well-known part of the book, the Cool-Girl rant.

“Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.”

Flynn’s crime thriller is creepy, amazing, and forces you to think. Why is it that Nick is lying to the police? Why was the blood cleaned up? Why, oh why, did Amy go to buy a gun on Valentine’s Day?

Like Gone Girl, Flynn’s other two works also portray their protagonists as dark characters. Camille Parker from Sharp Objects is “a narrator who drinks too much, screws too much, and has a long history of slicing words into herself”. She has a toxic mother, a thirteen-year-old half-sister who has easy access to drugs and alcohol, in a town where two girls have been murdered.

Libby Day from Dark Places has seen it all. Her mother and two sisters were murdered when she was seven. She testified against her brother, who was arrested for the murder of the three women, but is forced to revisit the past by a group obsessed with notorious crime cases, finding shocking revelations.

The appeal of Gillian’s writing is that she is willing to make every single person in a novel unsympathetic; dastardly, even. She acknowledges the dark side of her protagonists, mainly women, and challenges the notion of their innately caring, motherly nature. She goes on to explore another side of feminism ̶ one that not only involves girl power and being the best you can be, but also the ability to have female villains.

She is quite, if not completely, similar to Jane Austen in the late 18th and early 19th century. Her most renowned work, Pride and Prejudice, starts with the following line.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Austen undertakes a quiet rebellion in what she writes. Margaret Kirkham, author of ‘Jane Austen: Feminism and Fiction’ has argued that Austen is part of the feminist movement because, for one, her “heroines do not adore or worship their husbands, though they respect and love them. They are not, especially in the later novels, allowed to get married at all until the heroes have provided convincing evidence of appreciating their qualities of mind, and of accepting their power of rational judgment, as well as their good hearts.”

Morality, duty to society, manners, and religious seriousness, are central themes of Austen’s works. She explores the theme of marriage but seldom lets female characters make compromises for themselves.

Both Austen and Flynn’s writing is miles apart when concerned with their portrayal of women, but what unites them is their cause for feminism, and influencing their readers towards it by their work.