Have you ever wondered, why do classical dancers have to follow prescribed body ideals like long hair or big eyes? Why do these costumes, or the process of shringar differ for different genders? Each of these elements—the costume, the hair, the jewelry carry with them some story, history, and social implication in the present day.

Questions like these arose the curiosity of a Mohiniattam dancer, who, in her attempt to protest the prescriptions unravelled the inherent gender and caste politics within the Indian classical dance form of Mohiniyattam.

About Mohiniyattam, The Classical Dance

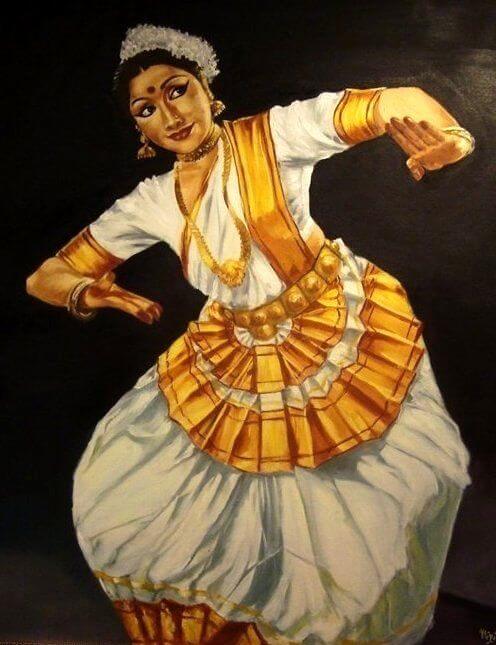

Mohiniyattam, also known as Mohiniattam, is an Indian classical dance form that has its roots in the south Indian state of Kerala.

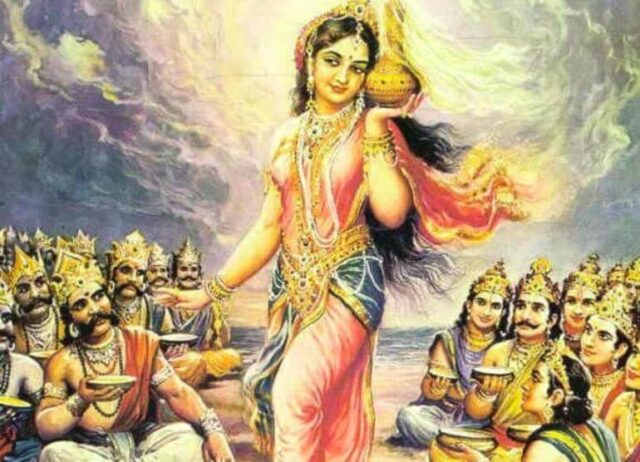

The term ‘Mohini’ is derived from Hindu mythology where goddess Mohini, a female avatar of Lord Vishnu appears in the epic tale of Mahabharata.

Mohini was a divine beauty, an enchantress who used her charms to help the devas (gods), ‘attam’ means movement, Mohiniattam, therefore, implies beautiful dancing women.

This dance form, like other classical forms, has evolved from ancient Sanskrit Hindu text called ‘Natya Shastra’ and is inspired by the Lasya type of dance that is more soft, graceful, and gentle.

It is conventionally performed solo by a female performer on Carnatic music.

Mohiniattam has had a troubled and complicated past. Under the patronage of the Maharaja of Travancore in the nineteenth century, the dance form developed was systematized and thrived but soon, it was discouraged and subjected to shame during colonial rule.

The dance was originally performed by devadasis in temples so, during the British rule, the disadvantaged socio-economic state of devadasis led people to attach negative connotations to Mohiniattam.

The Christian missionaries regarded devadasis as harlots and launched an anti-dance movement in 1892 in order to discourage all the dance practices.

After its stigmatization and decline, the dance form finally revived during the early 1900s when a nationalist Malayalam poet, Vallathol Narayan Menon, helped in repealing the ban on temple dancing.

Later, a Kerala Kalamandalam dance school was established to promote proper training of the traditional dance form.

The dance form finally got the respect it deserved after the contributions of great dancers like Mundraj, Krishna Panicker, Thankamony, Guru, and Kalyanikutty Amma.

The Classical Dancer Who Cut Her Hair

Sreelekshmi Namboothiri published an article on FirstPost titled ‘What cutting my own hair during a Mohiniyattam performance taught me about gender politics within the form’, that takes the readers on a journey to the dance form’s past, present, and beyond.

Through her experience and the performance, she explains her quest to find answers about the traditional rules in Mohiniattam in the new age society.

Sreelekshmi Namboothiri is a disciple of Dr. Jayaprabha Menon and has been the president of the International Academy of Mohiniyattam, she is currently pursuing M.A. in Performance Studies, she also has a bachelors in English Honors and has contributed to many magazines with her brilliant articles.

She gave a “protest performance” on 18th December 2020. Her performance was titled ‘Aattam’ as she questioned the implications of ‘Mohini’ in Mohiniyattam.

Also Read: Unique & Progressive “Period Room” For Menstruating Females In A Maharashtra Slum

Exploring The Classical

Sreelekshmi, in her article, enlightens the readers with the early history of the dance form which is not commonly known. Mohiniyattam was earlier called ‘Tevidicchi Aattam’—a fact that is not well known and has an interesting history.

Tevidicchi Aattam used to be performed by devadasis in temples, but when the systematization of Mohiniyattam in the post-colonial era took place, its technicalities were changed and altered to fit a particular framework of the body of a female.

The dance form was changed yet again in the 1960s when some of its choreographies were deemed vulgar, changes were done to the form by adding and subtracting elements as per the society deemed fit for a woman, majorly because of the original sensual portrayals through the art form.

The 1960s was a sophisticated era, most of the social change was a result of colonial hangover who did not believe in respectable women being “sexual”.

“Classical dances have certain body ideals created for themselves, and one of them is the long hair or a stipulated hair length for the female performer that qualifies her to wear the costume. What does the hair — especially the long hair attached to the body of the woman — imply?”

-excerpt from Sreelekshmi’s article

Currently, as Sreelekshmi informs, ‘Tevidicchi’ has become a derogatory term in Malayalam due to the appropriation by the upper-castes.

“The devadasis performed the dance of Tevidicchi Aattam in Kerala, which was later followed by upper caste appropriation of it with changes made to the art form, including its renaming and introduction of the figure of ‘mohini’. I still do not know if using the word ‘mohini’ with aattam feels right for me, and hence, I wanted to only use the term ‘aattam’ meaning ‘movement’. If I should be using the term ‘Mohini’-aattam anymore is a question I continue to ask myself.”

-excerpt from Sreelekshmi’s article

Is It Time For Yet Another Restructuring Of The Form?

Reading up extensively on Mohiniyattam made Sreelekshmi question the practice. She wanted to convey her doubts, she wanted to prove a point, and what better way to do so, than through the dance itself.

She narrated the traditional choreography of ‘Jeeva’ from her perspective, and added the element of cutting her own hair mid-performance, as a sign of rebellion, in order to feel liberated from these prescriptions set by the society in the 1960s.

“One may also want to note the differences in the traditional costumes for ‘men’ and ‘women’. At a time when we speak of genders as non-binary entities, how do we portray the same in dance? Is it then necessary for women to don the ‘female’ costumes? What did the costumes suggest in terms of gender performativity, and the form’s geo-socio-political locations? Additionally, did all these aspects strip Mohiniyattam of its essence or ‘Mohiniyattam-ness’? I did not think so.”

-excerpt from Sreelekshmi’s article

In the cultural context, from gendered elements to the upper caste appropriation of the form, she throws a light on all the ironies in the present-day Mohiniattam.

Her brave attempt makes us question—is it time to reconsider the traditional art forms, is it time for yet another change according to the current notions in society?

Image Credits: Google Images

Sources: CulturalIndia, FirstPost, Vedicfeed

Find The Blogger: @MNtweeting

This post is tagged under: Dance, Mohiniyattam, Mohinattam, tradition, culture, art, art and culture, Sreelekshmi Namboothiri, history, classical dance form, Indian classical dance, Carnatic music, Kerala, south India, Indian Mythology, Lord Vishnu, Upper caste, appropriation, gender politics, caste politics, reformation

Other Recommendations:

How The Indian Music Industry Is Losing Rs. 200 Crore In Revenue

Is it then necessary for women to don the ‘female’ costumes?