By Shruti Sharma

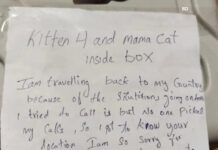

Around 6 years ago, a woman died at the age of 85 in a relatively isolated island group off the coast of the Indian subcontinent. Although there’s nothing particularly spectacular about that fact, the only caveat is that she was the last speaker of the ancient ‘Bo’ language in the Andaman Islands, one of the 10 great Andamanese languages which might be the last representatives of pre-Neolithic and Neolithic languages which originated in Africa. And as she took her last breath, she took to her grave an entire system of sounds, connected to a wider web of culture, traditions, customs and views, never to return again.

This is not just one isolated incident we’re talking about, the Bhasha Research & Publication Centre concludes that 220 Indian languages have disappeared in the last 50 years and that another 150 could vanish in the next 50 years as speakers die and their children fail to learn their ancestral tongues. Out of all languages spoken in India, 96% are endangered, restricted to only 4% of the population.

In a land which swears by the tag of ‘Unity in diversity’, what can be the possible reasons behind this?

‘Educating’ the ‘barbarians’

1. Power relations have always dominated cultural traditions. In order to exercise authority, education systems have been revamped in accordance with western ideas of what it means to be educated. Promoting a single language is also often seen as a way to foster national identity, however in India itself, we have seen how it has proved to be exactly the opposite.

2. Indigenous communities have been forced to interact with the ‘mainstream’, thrown out of their ancestral lands, only to encounter a situation where they now have to struggle for subsistence in a foreign system. The death of languages is a gradual process, with new generations finding no utility in learning languages in an atmosphere where their language is a liability.

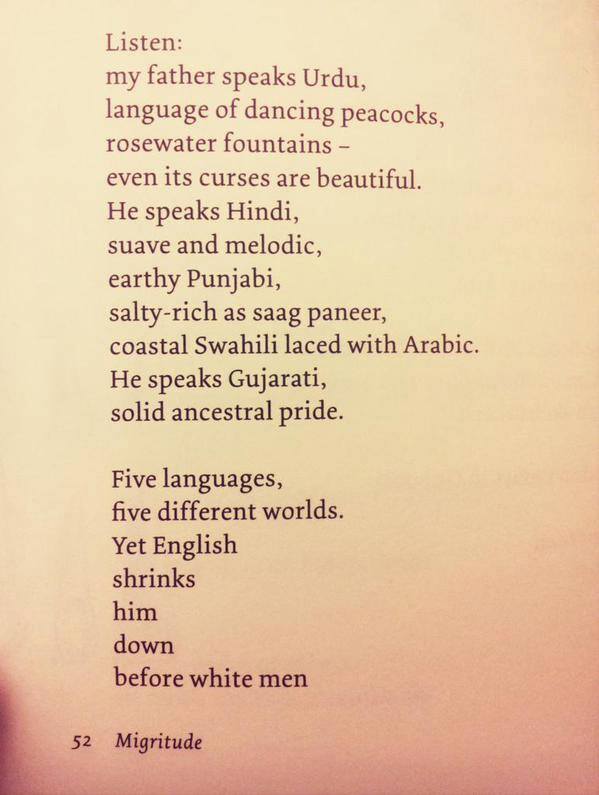

The speech spectrum has been fairly homogenised and shows no signs of stopping. English is the lingua franca of the ‘modern’ age, and those who use it in non-European, non-American countries as a second language overshoot its native speakers by millions. But the loss of languages passed down for millennia, along with their unique arts and cosmologies, may have consequences that won’t be understood until it is too late to reverse them.

And the sad part is, nobody gives a shit.

And why should they? The majority is clearly not affected. How does it matter that a few ‘uncivilised’ people lose their tribal languages and are gradually assimilated into the mainstream?

A. ‘Cause minorities matter too!

Simply the viewpoints of the privileged majority of the dominant language group are not the basis on which we should judge the importance or worth of a particular cultural or linguistic tradition, but the value endowed to it by the speakers themselves. Languages are not simply arrangements of sounds and alphabets, they are inextricably connected to the self-worth of a community and its cultural independence. Some words describe unique concepts, which cannot be translated to other ones, simply because of different worldviews associated with both.

Sample this:

1. ‘Aap’ and ‘ji’-However hard you try to respect people in English, the ‘you’ just puts everyone on a level playing field.

2. ‘Dharma’- this word has no equivalent in English, denoting a mix of religion, duty, the eternal law of the cosmos.

The moment a language disappears, the entire culture is lost, the distinct community disappears in its individual right and merely becomes part of a larger subgroup.

B. It is a loss to linguistics, psychology, anthropology and history where the study of languages is critical to understanding various unknown aspects of human thought. Languages hold important clues to the history of our species, thus decreasing our ability to understand our past.

C. Knowledge of biological diversity: When the marine biologist R.E. Johannes interviewed a Palauan fisherman born in 1894, he found that he had names for over 300 different species of fish, and knew the lunar spawning cycles of several times as many species as had then been described in the scientific literature.

D. It provides an insight into the intricate relationship between language and thought and increases overall knowledge systems. Every language provides its own “map” of the world. Some Eskimo languages have dozens of different words for ‘snow’. While English just uses the word ‘love’, Ancient Greek had four main words for love and dozens of minor words.

And thus, it’s also important to save endangered languages not merely for the love of diversity but to save ideas that can be expressed in no other way. Homogenous languages will gradually make us all into clones, restricting us to think in particular ways.

E. Because it affects everyone. In a land where a highly qualified individual in his own field can get nowhere without a knowledge of English and where modernity and efficacy are defined by fluency in a foreign language, the issue becomes all the more important.

What YOU can do:

Learn a language, try to know more about indigenous communities around you and respect and celebrate differences.

And learn English, but don’t wear it like a badge upon your chest.

Granted that English is a language that immediately connects you to communities across the globe, it doesn’t in any way make you superior to anyone else. Laughing at different Indian accents, taking pride in the fact that English is the only language one properly knows, “Dedh aur paune kya hota hai?” are characteristics so subtle but so widespread and chilling among people around me it’s not even funny anymore.

Heterogeneity is something that we need for society to evolve in the long run at a time when the ideas of ‘civilization’ and ‘development’ of native communities have been so contorted as to deny them the very rights that a nation stands for in the first place.

Images Credits: Google