Recently Sonia Gandhi’s dream bill, the Food Security Bill (FSB) was passed in the Lok Sabha as well as the Rajya Sabha, which guarantees 5 kg of rice, wheat and coarse cereals per month per individual at a fixed price of Rs 3, 2, 1, respectively, to nearly 67% of the population and also ensures benefits to pregnant women, lactating mothers and children. The food security bill aims to satisfy this basic wants and in that sense it encourages welfare economics. A critical analysis of its impact on the country’s economy can help us get a clearer picture of the act. The UPA’s ambitious food security scheme aims to provide food grain to about 800 million people at heavily subsidised prices. Critics question its fiscal sustainability and the politics involved.

The government estimates suggest that food security will cost Rs 1,24,723 crore per year. But that is just one estimate. Andy Mukherjee, a columnist with Reuters, puts the cost at around $25 billion. Economist Surjit Bhalla in a column in The Indian Express put the cost of the bill at Rs 3,14,000 crore or around 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Dr. Bhalla’s calculations have already been challenged on the ground that they contain errors. It takes into account the average consumption of PDS grain of entire population and not just PDS beneficiaries. Ashok gulati and his co authors in a report of the commission for agriculture costs and prices(CACP) have argued that to meet the requirements of the NFSA, the burden on the government will be about 6.8 lakh crore over 3 years(roughly 2.3 lakh crore a year).

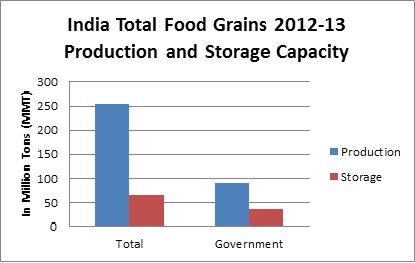

This estimate includes the agriculture production enhancement costs. The trouble here is that by expressing the cost of food security in terms of percentage of GDP, we do not understand the gravity of the situation that we are getting into. Inorder to properly understand the situation we need to express the cost of food security as a percentage of the total receipts(less borrowings) of the government. The government’s estimated cost of food security comes at 11.10% of the total receipts. The CACP’s estimated cost of food security comes at 21.5% of the total receipts. Bhalla’s cost of food security comes at around 28% of the total receipts. It is also worth remembering that the government estimate of the cost of food security atRs 1, 24,723 crore is very optimistic. The CACP points out that this estimate does not take into account “additional expenditure that is needed for the envisaged administrative set up, scaling up of operations, enhancement of production, investments for storage, movement, processing and market infrastructure etc.” Food security will also mean a higher expenditure for the government in the days to come (provided its an open ended scheme). A higher expenditure will mean a higher fiscal deficit. The question is that how will this higher expenditure be financed? Given that the economy is in a breakdown mode, tax rate cannot be increased. The government will have to finance it through higher borrowing which will have an effect on private borrowing. This means that the era of high interest rates will continue, which will further dampen the economic growth. Policymakers say that the government can find resources provided it cuts down or ends the oil subsidy to offset the additional burden arising out of the Food Security Bill. But the government is unlikely to do that, as it will not go well among the voters in an election year. Moreover reducing fuel subsidy will increase diesel prices, making the use of tractors more expensive. Cutting fertiliser subsidies will raise the input costs of agriculture. Each is connected with the other and there’s no free lunch in the system. This might also lead to the government printing money to finance the scheme, which will lead to higher inflation. Prices will rise due to other reasons as well. Government’s confirmed procurement will have some unintended consequences which the government is not taking into account. As the CACP points out “Assured procurement gives an incentive for farmers to produce cereals rather than diversify the production-basket…Vegetable production too may be affected – pushing food inflation further.” And this will hit the very people food security is expected to benefit.

Moreover we need to see if in a particular year when the government is not able to procure enough rice or wheat to fulfill its obligations under right to food security; it will have to import these grains. And buying rice or wheat internationally will mean paying in dollars. This will lead to increased demand for dollars and pressure on the rupee and will also widen the current account deficit. The weakest point of the right to food security is uncertainty involved in its implementation. NFSA will use the extremely “leaky” public distribution system to distribute food grains. A recent study by Jha and Ramaswami estimates that in 2004-05, 70 per cent of the poor received no grain through the pubic distribution system while 70 per cent of those who did receive it were non-poor. Another grey area is related to the identification of the beneficiaries.While the act suggests that identification has to be done by the states, most state governments are not clear about how and on what basis should the beneficiaries be identified.Economists have provided suggestions over the issue- instead of identifying the poor, make PDS universal but exclude the clearly identifiable rich, so that all poor will be covered even at the cost of some undeserving rich getting covered. This was adopted in Chhattisgarh and has been praised for reducing the amount of grain lost by pilferage and through corrupt practices. However this will increase the fiscal burden, but we actually need to weigh the costs and benefits of the system. Or through the use of advanced technology, linking the system to aadhar card ( although that will take at least 2 years) leakages can be reduced.

To conclude, what India actually needs is not a new setup of food security act replacing existing PDS but improved delivery mechanism. If the government goes in for enlarging the public distribution system without revamping it, where is the guarantee that the intended food grain will reach the poor? So how hopeful is the adoption of the food security bill without bringing any radical changes in the public distribution system and without acknowledging the major hurdles in its implementation, is a big question that still remains unanswered.