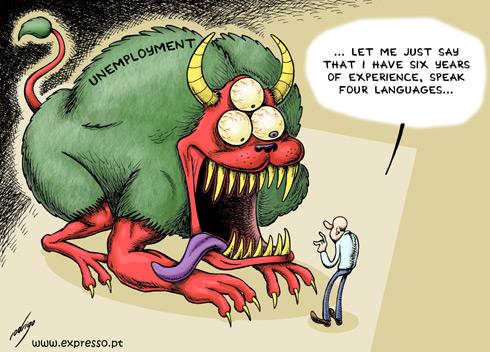

There has been considerable debate in India about the impact of growth on employment especially in the organized manufacturing sector for different periods since the early 1980s. For the period as a whole as well as for these two separate periods – the pre-and post-reform phases-the picture that emerges is one of “jobless growth”, due to the combined effect of two trends that have cancelled each other out; one set of industries was characterized by employment-creating growth while another set by employment- displacing growth.

Over this period, there has been acceleration in capital intensification at the expense of creating employment. A good part of the resultant increase in labour productivity was retained by the employers as the product wage did not increase in proportion to output growth. The workers as a class thus lost in terms of both additional employment and real wages in organized manufacturing sector.

This may reflect the lack of recognition of women’s work among the investigators, as has been claimed. But self-employment has also fallen for men, and so this could also be related to declining viability of small-scale activities, since much of the recent economic growth has been corporate driven. The slowdown in job growth was not only in agriculture, where it could be expected, but in non-agricultural activities, where the rate of employment growth has nearly halved from 4.7% annual rate to 2.5%. Regular paid work (that is work done on a regular basis for an employer, whether in the formal or informal sector) has barely increased, and so the big increase has been in casual work, which tends to be based on daily contracts, and is therefore extremely fragile and unprotected. Organized employment is likely not to have increased much at all, despite the massive explosion of incomes in the organized sector (which have largely accrued to profits).

Does an increase in the growth of the tertiary sector truly indicate economic growth?

The sectoral segregation of national income shows that the tertiary sector has grown relatively faster than the other sectors throughout the post independence period of the Indian economy. The demand of services and manufactures being more elastic than that of agricultural products, the process of development is said to have witnessed such shift away from agriculture. The question then arises as to whether this pattern of growth in India can be sustained without serious implications on inflation and income distribution.