The years have done little to lessen the perception among many, especially in the West that the Middle East is a cauldron of chaos, an acronym for anarchy disguised as a loose federation of nation-states. From the revolution in 1979 to the Arab Spring, the region has always been a hotspot of radical overhaul, changes that have never hesitated to shy away from the barrel of the gun. As the first bombs fell on Sana’a, the largest city in Yemen on the 25th, so began the latest episode in the dark and bloody history of the Middle East. And yet, even in the first few days of this ‘international’ conflict, the unfortunate expectation of an awaiting long-drawn conflict says volumes about the hopelessness that precedes events of significance in the region.

Who’s fighting whom?

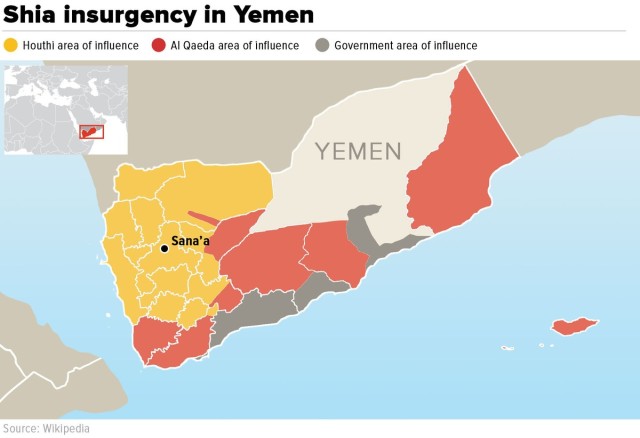

The Gulf Cooperation Council, led by Saudi Arabia and supported by the likes of Egypt, Jordan, Sudan and the UAE, led the charge as the first air raids rained carnage on the already battered country on the southern end of the Arabian peninsula. This ‘military intervention,’ supported in different capacities by nations such as the USA, UK and Israel apparently attempts to restore President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi to power, after he was deposed in an unconstitutional coup by the Houthis, a Zaidite Shiite group native of the same country. However, what looks like the case of a common coup is far from it, and what most observers including many involved in the planning of Operation Decisive Storm have chosen to ignore is the sheer complexity and numbers of the players involved in the bloody chapter being written in the sands of Yemen.

Although the battle lines in Yemen are primarily drawn between Hadi loyalists and the Houthis (who allegedly also enjoy the support of Saleh, the ex-President of Yemen, also a Zaidi), it has also seen a spate of activities from the side of the Al-Qaeda of the Arabian Peninsula or the AQAP and the Yemeni arm of the Islamic State. What’s more, it is alleged that much of Houthi success in Yemen can be attributed to the funding, arms and training provided by Iran.

A Proxy-war in the making

With the entry of Saudi Arabia, Yemen has become a playground for a proxy war between the Wahabist-Saudi Arabia (an offshoot of Sunni Islam) and Shiite-Iran (Although the extent of Iranian involvement is questioned by US intelligence). The entire military and political calculations of capabilities of the GCC are based primarily on the assumption that Iran will not back down from its alleged proxy war in Yemen. It is perhaps a result of this fear that regiments of the Saudi Army stand on alert on the porous border the country shares with Yemen, with another army battalion from Egypt soon expected to join them. Surprisingly, Israel has come down in support of the Gulf military intervention, primarily because like Saudi Arabia, it feels existentially threatened by the Islamic State of Iran. Iran’s nuclear plans have long been a source of concern for Israel and even as talks of a nuclear deal continue between Iran and the West, if Prime Minister Netanyahu’s speech in the U.S Congress is any indication, it remains unwilling to let go of its vitriolic against Iran.

There may or not be truth in the extent of Iranian involvement in the Yemen crisis. However, if history is any reminder, any involvement by Iran is going to be significant. Consider the case of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Although Shiite-Iran and a predominantly Sunni-Islamic State are for all intents and purposes mortal enemies, Iran’s direct actions in helping Assad(An Alawi Muslim, an offshoot from the school of Shia Islam) stay in power in Syria have further marginalised the Sunni-majority and indirectly emboldened the rebels and the Islamic State (A case reminiscent of Syrian involvement in the Lebanese Civil War). If however, a full-blown proxy war does start in Yemen, it will lend an unfortunate credence and inevitability to the state of undeniable collapse that awaits the country, as predicted by the UN High Commissioner.

However, as much as the responsibility for the conflict falls on the shoulders of native militias in Yemen, blame substantially does fall on Saudi Arabian shoulders as well. As perhaps the most powerful country in the region, there is no nation-state in the region more adequately equipped to deal with a spiraling crisis in the region. However, its perception of the Yemeni crisis as a proxy war rather than a domestic crisis has hurt it. Rather than using the might of the Gulf Cooperation Council to bring the illegitimate Houthiite government to the negotiating table, it has used its armed forces to bomb them into a growing column of debris. This might however, have been directed against the AQAP and the IS considering the fact that unlike them, the Houthis are indigenous to Yemen, a reality that reflects that they cannot and must not be defeated militarily in a country which is their home. It is essentially, an over-reaction on the part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the Houthiite advance in Yemen, which also opens up the possibility of a ground invasion (Although the chances of its success are suspect considering the ill-training of the Saudi troops). And it is this over-reaction that is costing the war against terrorist organisations like the AQAP and the IS, which have been taking advantage of the collective Gulf distractions, expanding all across Southern Yemen.

The struggle for relevance

The struggle for relevance and influence between the AQAP and the IS too is a curious study. Al-Qaeda traditionally, has been the face of terror for the better part of the 21st century. However, with the meteoric rise in notoriety of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, Al-Qaeda, especially after the death of Osama Bin Laden, has struggled for relevance. However today, even the IS has its operations such as the advance of Baghdad halted in its tracks thanks to the US intervention. In fact, the Islamic State’s stall is best reflected by the liberation of Tikrit from its hands by the Iraqi forces. Which is why, the IS like the Al-Qaeda is looking to stretch its propaganda and its sphere of influence elsewhere, across the world. Now, although the IS has accepted oaths of fealty from many groups across the world, only the Boko Haram in Nigeria is strong enough to be impactful. What the bomb blast in Sana’a reflects is that the IS, perhaps more than the AQAP will go to any extent to make its mark on Yemen, a realization that makes the Saudi endeavor to target just the Houthis and not the extremists all the more appalling, considering their own sketchy record in tackling Salafist and Wahabist extremism. Even the USA seems to have taken a few steps back from their position a few years ago when they were actively involved with the then-President Saleh to use drones to bomb AQAP targets in Yemen.

USA on the backseat?

Speaking of the USA, the American response to the chaos in Yemen has been strangely and relatively quiet. Publicly, the Obama Administration has always congratulated itself on the so-called success of the ‘Yemen Model’ to combat terrorism. The fact that this self-congratulation was a mere few days before the fall of Sana’a to Houthi rebels reflects the US ignorance of ground realities in the Middle East and the short-sightedness of its foreign policy. For perhaps the entirety of the Obama Administration, the question of an open war using ground troops abroad has long been considered political suicide (A truth tempered by the historical experience of American adventures in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq). Which is why, US foreign policy in the Middle East has revolved around the poisonous concoction of armed proxies (Or as some analysts say, pansies) and drone strikes, the use of short-term solutions to treat long-term problems and crises. In Yemen for instance, the US supported an undemocratic President Saleh for decades, and later his equally undemocratic successor Hadi, in the hopes that this support will translate into efforts against the dominant Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. However, other than a couple of drone strikes, these efforts have been non-becoming, and with the fall of Sana’a and the evacuation of the US Special Forces, the extremists have only been further emboldened. This minimalist policy, as President Obama terms it ‘Don’t do Stupid Shit’ theory can therefore hardly be called a template for success. The USA and the world at large therefore must be wary of this ‘success story’ being replicated across the Middle East as a template to combat terrorism because, quite frankly, it doesn’t work.

Geographically-located directly opposite to the Horn of Africa, and arching the entry to the Red Sea, and by extension the entry to the Suez Canal and Europe, the strategic geo-political importance of Yemen cannot be understated. The Yemen crisis may just be another domino in a series of perpetual anarchy that is identified with the Middle-East, but it has shown the potential to mutate into something more devious, with the country being the playground of a proxy war waged by other countries. It is therefore, up to the global community to halt this campaign of proxies and pansies, and bring a semblance of normalcy to the war-torn country. Yemen already has enough on its plate, let alone a military intervention by people they consider foreign. Negotiations must ensue, not a unilateral or a bilateral conference, but a negotiation that reflects and represents the aspirations of all. That is what nations like Saudi Arabia must strive to do, and not add on to the pile of debris that has buried Sana’a. A lot remains at stake here, including the stability and future of the Middle-East and International trade, with Oil prices especially being affected considering the difficulty of freight passage through a war-torn region.

The fact that over a couple of years after the Arab Spring, the Middle-East is still grappling with reform in social and political institutions is reflective of not just the deep-seated condescension its society has with change, but also the complacency of nation-states in power such as the USA and Saudi Arabia towards its primordial foreign policy initiatives. Change must come, not just a surface-check of policies, but a systematic overhaul of existing notions, attitudes and perceptions.