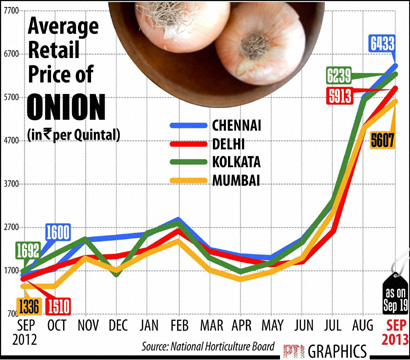

Rupee facing an all time low, Mr. Raghuram Rajan taking over as the handsome governor of the central bank, AAP emerging as the wild card entry of “The Great Indian Political” reality show, India roaring NaMo NaMo are some events that swept India off its’ feet in 2013. While mentioning these, one cannot forget to mention the “onion story”. Oh yes, the trials and tribulations faced by onions define a roller coaster ride with onion prices rising to Rs 100 per kg to hitting the floor at some Rs 20 per kg now (retail price). Last year saw housewives finding it hard to manage their monthly budgets and minimizing onion usage from their lunch and dinner tables. Not only is onion an essential ingredient in one’s meal but also in the past decades, onion has gained political significance wielding enough power to bring down governments.

Although imposing MEP implies that the consumer surplus will increase, at the same time the producer surplus will decrease and a deadweight loss will be incurred. Simply put, the minimum export subsidy will increase the price at which the domestic producers sell their goods in the international market. This might bring the demand and supply model closer to the world price. The repercussions of the same will be that India will lose its comparative advantage in the production of these goods in case the minimum export price is binding. The government expects such a policy to help in stabilizing prices, however, as mentioned above; such a policy would only benefit a certain strata of the economy and on the whole will result in fall in the total Surplus. MEP hampers the interests of farmers and gives them a hard time. There was a lot of hue and cry among farmers in the major producing states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat and India witnessed several protests and strikes by them. Farmers were bleeding when they had to sell the fresh produce at Rs 10 per kg when their investment came around some Rs 11. Responding to the same, on December 26th last year, the government reduced minimum export price (MEP) of onion to USD 150 a tonne from USD 350 to boost shipments and check sharp fall in domestic prices. Also the MEP policy leads to a fall in exports against the rising demands for imports widening the trade deficit and piling on to the already high current account deficit of 4.8% of the GDP. India at its present state cannot afford any further decrease in its foreign reserves.

The government has to intervene somewhere to ensure price stability but also availability of onions to domestic consumers. It has to ensure justice to both the farmers and the consumers. It is a difficult trade off. It is the ever prevailing policy dilemma.