Hello after a very long time. In my last two articles I’ve introduced & made you familiar with a rather amazing figure in human history. A man, who was no less than a complex mystery box for many people, for many years. The Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick was hailed as half man & half elephant because of his extreme, one may say, physical deformities. He was displayed throughout Europe as a curiosity exhibit & was somewhat successful. In this article, the third & the last about him, I wish to throw light on the events that continued in his life in the London Hospital, his death & the legacy he left behind.

So, picking up from where we left…

In the hospital it was discovered by Frederick Treves that Merrick’s physical condition had deteriorated over the years & that he had become quite crippled by his deformities. Treves also suspected that Merrick now suffered from a heart condition & that he only had a few more years to live. His general health improved under the hospital care & though earlier some nurses were initially upset by his appearance, they overcame this & cared for him; & Treves finally developed an understanding of Merrick’s speech.

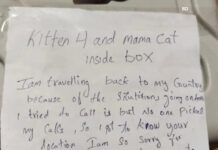

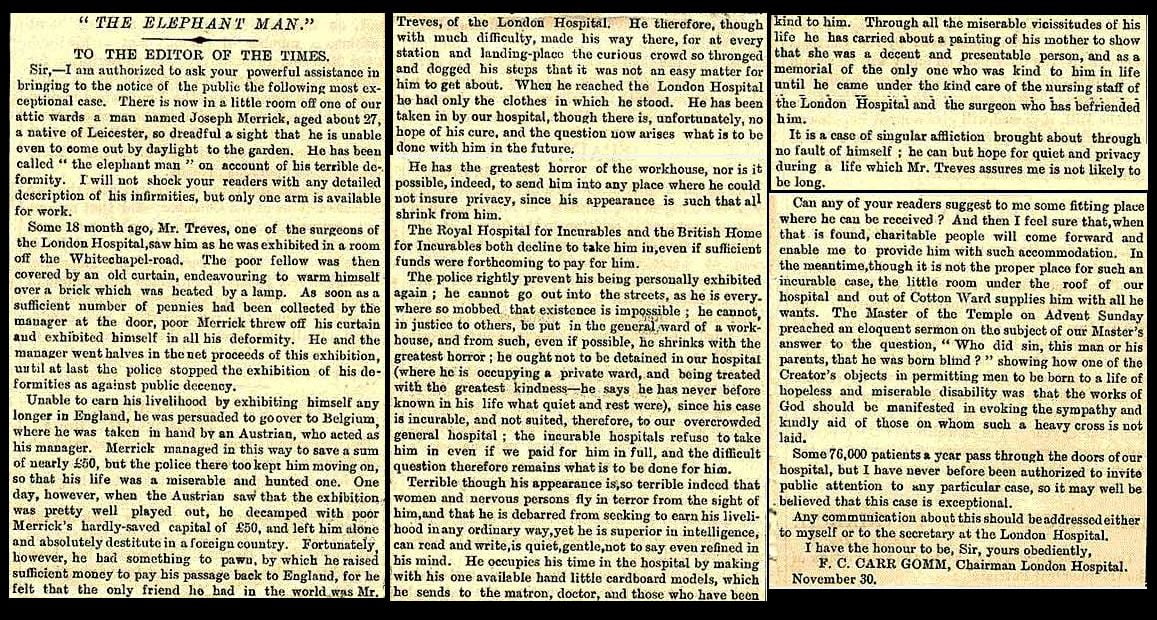

Merrick’s long term care was a major concern for the Hospital as it was not fully equipped for chronic cases. Carr Gomm, the chairman of the hospital committee contacted other institutions and hospitals only to be disappointed. Then, Carr Gomm wrote a letter to The Times, printed on December 4, outlining Merrick’s case and asking readers for suggestions. The public response in letters and donations was significant and the situation was even covered by the British Medical Journal. The support for Merrick was enough for Carr Gomm to convince the committee to keep Merrick in the hospital’s care for the remainder of his life. He was moved from the attic to two rooms in the basement adjacent to a small courtyard. The rooms were furnished to suit Merrick, with a specially constructed bed and no mirrors (at Treves’ instructions).

(Carr Gomm’s letter to The Times)

Treves and Merrick developed a friendly relationship and Treves visited him daily and spent a couple of hours with him every Sunday. He observed that Merrick was very sensitive and showed his emotions easily. At times he was bored and lonely, and demonstrated signs of depression. He spent his entire adult life segregated from women, first in the workhouse & then as an exhibit. Most women he met were either disgusted or frightened by his appearance & his opinions about women were based on his memories of his mother and what he read in books. Treves then arranged for a friend of his named Mrs. Leila Maturin, “a young and pretty widow” to visit Merrick.

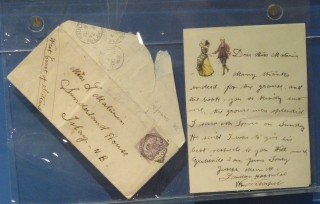

(Merrick’s letter to Leila Maturin)

Their Meeting was short, as Merrick was quickly overcome with emotions. He later told Treves that Maturin had been the first woman ever to smile at him, the first to shake his hand. She kept in contact with him and a letter written by him to her, thanking her for the gift of a book and a brace of grouse, is the only surviving letter written by Merrick. Merrick was curious to know about the “real world” and questioned Treves on a number of topics, & one day he expressed his desire to visit a “real” house, Treves obliged by taking him to visit his Wimpole Street townhouse and meet his wife. At the hospital, Merrick spent his days by reading, constructing models of buildings out of card, & entertaining visits from Treves & his house surgeons. He woke up every day in the afternoon and would leave his room to walk in the same adjacent courtyard, after dark.

(Card church replica built by Merrick)

Due to Carr Gomm’s letters to The Times, Merrick’s case attracted the notice of London’s high society. One person who was interested was the actress Madge Kendal & although she never met Merrick in person, she was responsible for raising funds and public sympathy for him. Many other men and women of high society did visit him, and Merrick reciprocated with letters and hand-made gifts of card models and baskets. Merrick enjoyed these visits and became confident enough to converse with people who passed his windows. At times, he would leave his quarters and explore the hospital. When discovered, he was always hurried back to his quarters by nurses, who feared that he might frighten the patients.

On 21st May 1887, the Prince and Princess of Wales were to come to the hospital to officially open two newly finished buildings. Princess Alexandra wished to meet the Elephant Man, so after a tour of the hospital, the royal party went to his rooms for an introduction. The princess shook Merrick’s hand and sat with him, an experience that left Merrick overjoyed. She gave him a signed photograph of herself, which became a prized possession, she sent him a Christmas card each year. With the help of Madge Kendal, Merrick’s wish to visit the theatre was fulfilled. According to Treves, Merrick was “awed” and “enthralled”.

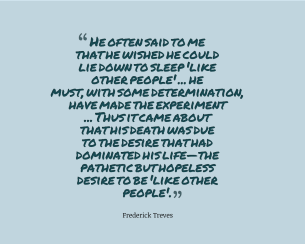

Merrick’s condition deteriorated over his four year stay at the London Hospital. He required a great deal of care from the nursing staff & spent much of his time in bed or sitting in his quarters. His facial deformities continued to grow and his head became even more enlarged. He died on April 11, 1890 at the age of 27. Merrick’s death was ruled accidental and the certified cause of death was asphyxia, caused by the weight of his head as he lay down. Treves, who performed an autopsy on the body, said that Merrick had died of a dislocated neck. Treves dissected Merrick’s body and took plaster casts of his head and limbs and mounted his skeleton, which remains in the pathology at the Royal London Hospital. Although the skeleton has never been on public display, there is a museum dedicated to his life housing some of his personal effects.

Medical Condition:

Ever since Merrick’s days as a novelty exhibition Whitechapel Road, his condition has been a source of curiosity for medical professionals. Dr. Henry Radcliffe Crocker, a dermatologist proposed that Merrick’s condition might be a combination of Dermatolysis, Pachdermatocele, & an unnamed bone deformity, all caused by change in nervous system. Crocker wrote about Merrick’s case in his 1888 book Diseases of the Skin: their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment.

In 1909, dermatologist Frederick Parkes Weber wrote about Recklinghausen disease (now known as neurofibromatosis type I) citing Merrick as an example. Symptoms of this genetic disorder include tumours of the nervous tissue and bones, and small warty growths on the skin. One characteristic of neurofibromatosis is the presence of light brown pigmentation on the skin called café au lait spots. These were never observed on Merrick’s body .Neurofibromatosis type I was the accepted diagnosis through most of the 20th century, although other suggestions included Mafucci syndrome and Polyostoic fibrous dysplasia (Albright’s disease).

In a 1986, Michael Cohen and J.A.R. Tibbles put forward the theory that Merrick had suffered from Proteus syndrome, a congenital disorder identified by Cohen in 1979. They cited Merrick’s lack of reported café au lait spots and the absence of any histological proof that he had suffered from neurofibromatosis type I. Unlike neurofibromatosis, Proteus syndrome affects tissue other than nerves, and it is a sporadic disorder rather than a genetically transmitted disease. In a letter to Biologist in June 2001, British teacher and Chartered Biologist Paul Spiring speculated that Merrick might have suffered from a combination of neurofibromatosis type I and Proteus syndrome.

The possibility that Merrick had both conditions formed the basis for a 2003 documentary film entitled The Curse of The Elephant Man. During 2003, the film makers commissioned further diagnostic tests using DNA that was extracted from Merrick’s hair and bone. However, the results of these tests proved inconclusive and therefore the precise cause of Merrick’s medical condition remains unknown.

The Legacy of Joseph Merrick:

In 1923, Frederick Treves published a volume entitled The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, in which he detailed what he knew of Merrick’s life and their personal interactions. This account is the source of much of what is known about Merrick, but there were several inaccuracies in the book. Merrick never completely confided in Treves about his early life, so these details were consequently sketchy in Treves’ Reminiscences. A more mysterious error is that of Merrick’s first name. Treves, in his earlier journal articles as well as his book, insisted on calling him John Merrick. In 1971, anthropologist Ashley Montagu published The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity which drew on Treves’ book and explored Merrick’s character. Montagu reprinted Treves’ account alongside various others such as Carr Gomm’s letter to the Times.

In 1980, Michael Howell and Peter Ford published The True History of the Elephant Man, presenting the fruits of their detailed archival research. Howell and Ford brought to light a large amount of new information about Merrick. In addition to proving that his name was Joseph, not John, they were able to describe in more detail his life story. They refuted some of the inaccuracies in Treves’ account, showing that Merrick’s mother did not abandon him, and that Merrick deliberately chose to exhibit himself to make a living.

Between 1979 and 1982, Merrick’s life story became the basis of several works of dramatic art based on the accounts of Treves and Montagu. In 1979, a Tony Award winning play, The Elephant Man, by American playwright Bernard Pomerance was staged. The character based on Merrick was played by Philip Anglim, and later by David Bowie, Mark Hamill and recently by Bradley Cooper. In 1980, David Lynch released the film, The Elephant Man, which received eight Academy Award nominations. Merrick was played by John Hurt and Frederick Treves by Anthony Hopkins. In 1982, US television network ABC broadcast an adaptation of Pomerance’s play, starring Anglim.

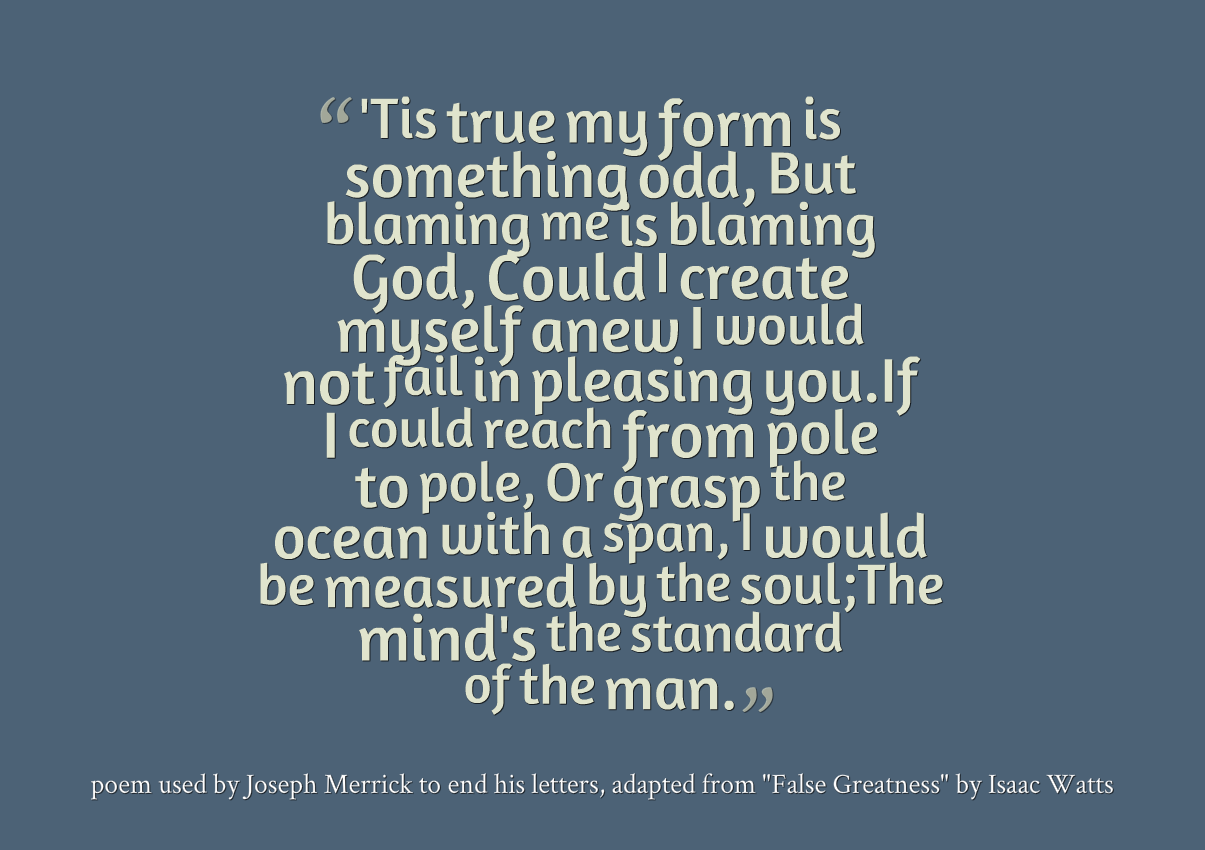

And with that said I arrive at the end of this article. It’s been amazing reading and even more thrilling writing about Mr. Merrick. Hope you guys had fun. I leave you with a beautiful poem that Merrick used to end his letters.

And till my next article…

Remember…Stay curious and keep that head bangin’!!!