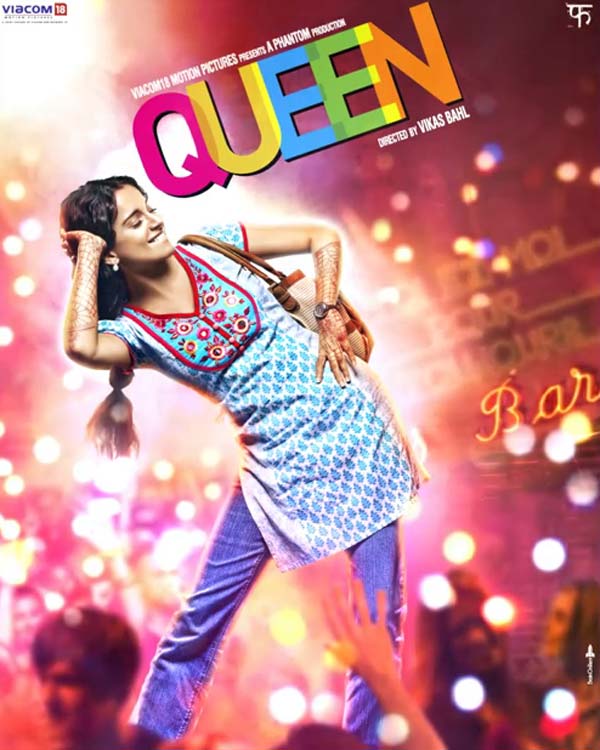

Though it seems innocuous that the title of the film is ‘Queen’, it has a deeper significance and is part of an ideology that informs the entire movie, and it is so subtle that most of us miss it. It unravels, in a multi-layered way, the two-sided interaction of East and the West, most obviously because the movie is not named after the protagonist (‘Rani’), but on her nickname (‘Queen’) given to her by her fiancé Vijay. It seems odd, if you really think about it.

The identity of an individual in a language is expressed through her/his name, and a manipulation of the name is a form of suppression on a mental, and thus a fundamental level. For example, the practice of adopting her husband’s surname is a form of the wife’s subjugation to the overarching male order. Only in this case, Vijay is shrewder. His act of naming her Queen is also based on a powerful class-consciousness that befits a once colonised nation. By calling her Queen, Vijay expresses discreetly, through flattery, his desire for her to transform into a woman who lives up to his ‘ideal’ standard: one who is beautiful, appears upper-class by looking ‘modern’ or wearing Western clothes; but who is also as homely and submissive like a traditional Indian wife. A Queen denotes an independent and powerful entity, autonomous and authoritative; but here this very term is cleverly reduced to mean only a trophy wife entirely under a man’s control, so much so that he gives her a name. This reduced version of a queen is a mere figure-head, meant to be treated like a slave in private, and a status-symbol in public; and Vijay desires to do just that. Therefore, rather than a woman emancipated, the title ‘Queen’ actually represents initially and in the Indian context, a woman subjugated and oppressed by patriarchal domination.

The impact of the West upon the Indian male psyche has not loosened their age-old assumptions about women. It has only become mixed up with the Western expectations of a woman as a sex-symbol, and has spawn a blatant hypocrisy. A woman must look modern, but underneath that ‘sexy’ exterior she has to behave in a traditional and ‘Indian’ manner. This hypocrisy is the movie’s primary theme, and the usage of the name Queen exposes it as mentioned above, but it also ultimately subverts it. And these two opposing and continuing processes visually shown to us through Rani’s transformation are grounded in and informed by a larger socio-economic history of the nation.

This particular double-standard of patriarchy is symptomatic of an India suffering from an acute identity-crisis. During and shortly after the British colonial rule, Indians did not face a threat of identity. While the concept of India as a nation itself emerged by the late 18th century; both before and after this formulation the people of India had their own traditions and cultures which were adhered to with or without British influence; and these roots were only strengthened during the freedom-struggle. Agreed, the Western influence in education and lifestyle was apparent, but only in the upper-classes, who reflected Western styles to consolidate their status and position over traditional India. Cricket seeped into India in a similar manner. The provincial princes and Kshatriya classes played the sport to be deemed superior and to establish ties with the ruling British. All of it was essentially a power-play, literally. But the majority of India defiantly remained seeped in its indigenous culture and traditions, up until recent times.

Tremendous political, economic and sociological changes in last few decades have led to India receiving and absorbing, through the market, media, arts and technology, the influence of Western thought, idioms and culture. The phenomenon is not restricted to India. Indeed, the world has become a global village, with a transfer of cultures to and fro from one part of the globe to another. The youth which grew up after 1991 has been impacted the most by these changes. Sociologically, the middle-classes have shown the most transformation. In the recent years, the widespread reach of the media has also enabled the penetration of Western media and culture into the vast expanse of India.

It is but natural that such an exposure would exacerbate confusion around the identity among the youth (especially those of and above the middle-class). Indian society is, as it were, and more acutely than before, stranded between two polar opposite cultures of the West and the East.

We ape the West superficially for social respectability and higher status, like the princes and Kshatriya clans playing cricket with their masters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And yet we attempt to hold onto our traditional and sometimes oppressive Indian traditions for security and cultural capital. The affluent are not the only victims of such a paradoxical and contradictory affliction. When Rani has a nightmare of Vijay reiterating that he could not marry her because their status did not match, one of his avatars was that of a bus conductor. Vijay’s condition is therefore not particular to his class, but is all-encompassing. It is a social comment on the rest of us who believe, whether rightfully or not, that Western influence is benefiting our country economically and socially, in addition to raising India’s international status. And this very confliction is but naturally projected on women in India as well.

Such an influence is advantageous in many ways too. And Queen depicts this profitable result of Western influence on the condition of women of the middle-class and above. Not only does Rani discover her identity, independence and freedom in an alien and European place, she is also aided by those who though belonging to other traditions and cultures are also drifters like her. The first one is Vijaylakshmi, who is, not accidentally, a mixture of Indian, French and Spanish blood. She offers Rani a cultural abode wherein a traditionally brought up/brainwashed woman like Rani can let her hair down and open her mind. In this space Rani not only conquers her prejudices against alcohol, pre-marital sex, revealing clothing, un-lady-like behaviour in public and children outside of marriage, but Vijaylakshmi’s influence also endows Rani with the confidence for self-expression and makes her bond with her. It is not surprising that Vijaylakshmi’s wild and ‘hippie’ lifestyle is made understandable to the more conventional Indian audiences by her mixed blood. It appeals to the audiences who do not regard her as a serious threat to their order, but as a sexually unrestrained exotic beauty in a foreign land. (Such a portrayal also appeals to their prurient instincts.) But they are proven wrong in their estimation of the influence of Vijaylakshmi – her influence on simpleton Rani is deep and abiding; and through her, it facilitates in the de-stabilization of the very traditional patriarchal order which they believed a woman like Vijaylakshmi, by virtue of her outsider status, had no influence over. We see a freer, unrestrained and independent Rani, one who is unafraid to walk the dark alleys, party till late or consider herself as an independent sexual and financial agent. Having benefited from Vijaylakshmi’s company, Rani also finds that she has some advises to offer to her too.

It is at this stage that Rani achieves a delicate balance. She refuses to be mentally or physically subordinated and hesitantly embraces her sexuality in a timid manner. At the same time, she retains her feminine modesty, and attempts to illuminate to Vijaylakshmi through the Indian lens the pitfalls of leading a lifestyle that is free, but devoid of duty and stability.

If liberal thought and expression, and unsuppressed sexuality are the West’s gift to the Indian women; the order, stability and wisdom of an ancient tradition is East’s contribution to the weak and fractured Western family system. While two females brought up differently bond with each other, there is a mutual lesson that both Rani and Vijaylakshmi learn through their interaction. Seen thus, the depiction of women in Queen, each absorbing cultural lessons from the other, is one of the positive aspects of the deepening of the social and political ties of India with the West, and is also the enduring quality of this movie.

Afterwards, both Vijaylakshmi and Rani undertake, in their individual capacities, their steps towards self-knowledge. This in itself is a Western trope. Whereas in the West the individual self and its desires are prioritized above its social self, it is the exact opposite in the Indian tradition. The destination of self-knowledge in the Western tradition is individual freedom and independence; conversely in the Indian tradition it is an infusion of the individual into a larger, greater social whole. The former is achieved through individualistic pursuit of self-knowledge; in the Indian tradition, such a path is paved by religion and dharma, or duty. Therefore, Rani’s and Vijaylakshmi’s attempts to know themselves locates the film in a strictly Western tradition. Queen, then, becomes a movie about the Indian tradition benefiting from and evolving because of Western influences. This is apparent not only in its story and theme, but also in its art and framework; in literary terms, the movie is Rani’s bildungsroman, or a coming of age story, like the English literary classics Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. Approached thus, Queen is more of a Western movie than an Indian one.

The Western moralizing edict in the film only expands as Rani reaches closer to her destination. For example, Rani’s interaction with the three men of her hostel (Russian, Japanese and French respectively) directly critiques the Indian men Rani has fraternized with since her childhood. Whereas in India men are either regarded as protectors or as direct threats to a woman’s safety, these ‘cultured’ and chivalrous men respect a woman’s space, independence, freedom and identity. Ultimately, it is the Russian, Alexander, who defends Rani from the aggression and oppression of Vijay, and if there is more direct dig at Indian men on an international level, I am yet to see it. A similar example is the Italian chef who begins as a patronizing and intimidating figure, but eventually offers Rani a platform upon which she can utilize her traditional Indian cooking skills to compete at an international level.

The fact that Rani wins the challenge is not meant to show the superiority of the Indian cuisine. It is an oblique attack on the Indian patriarchal system which expects women to be faultless domestic cooks (even though Rani helps in her father’s business at the sweet shop, she is not regarded as its successor due to her sex), but restricts them from using their talents towards advancement of their personal as against familial careers. (It isn’t a coincidence that a majority of professional chefs on television and in the culinary business are men. Maybe in this aspect, India is similar to the rest of the world.) It is by linking culinary expertise with the self-validation of a traditionally brought up Indian women that the movie breaks the western stereotypes. The West may continue to moralize but in the movie, it has some lessons to learn from India as well.

If there is a single underlying hypocrisy that Queen exposes and undercuts, it is the Indian concept of modernity. When Rani, wearing a dress, meets a forlorn Vijay at a cafe in Amsterdam, Vijay compliments her on her Western attire by calling it ‘modern’. Vijay’s mother herself expresses her sly delight in Rani’s attire when Rani goes to visit Vijay in India. As mentioned earlier, the double standards of patriarchy are exposed and subverted by such a portrayal. It was Rani’s modernity which ignited Vijay’s latent passion and propelled him in pursuit of her across the continent. But it is this same modernity which also cements Rani’s will to reject his amorous advances that do also have the backing of, in a true Indian tradition, Vijay’s family. Her modernity, or Western outlook, is not skin deep, like his. She achieves a fragile balance of two diverse cultures by announcing her autonomy, while he relies on the Western appearance, not its liberal values, to further his social status. This balancing act is the example that the movie sets for emulation – for both sexes.

And immediately, the meaning behind the name Queen transcends its enclosed patriarchal construct and evolves into a modern ideal which many of us unconsciously try to achieve: that of the true Indian Queen/King, who is independent, liberal and free by virtue of liberal Western education, but still rooted to her/his traditional structures; a perfect amalgamation of the East and the West. Rani’s evolution from an oppressed, traditional Indian woman to that of an independent and confident woman is the story of her evolution possible due to the example of the Western notions of freedom and independence and also her traditional outlook and wisdom, which are the products of the ancient Hindu tradition.

The movie cuts through Indian prejudices and oppression in India via a Western knife, like the British did against sati and the condition of widows in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The only difference is that by virtue of the modern phenomenon of the global-village, the West learns from the East as much as we learn from them. We are borrowing Western traditions, soaking them in our multi-coloured Indian social landscape and synthesising a unique fabric of our own to wear. Therefore the movie is titled Queen, and not Rani, but one day, even a Hindi title Rani will symbolize all that its Anglicized version once did. Such a transformation will require a major shift in the cultural and social landscape of India, and only the heavenly powers know if this would signify a complete erosion of our unique culture, or world peace.

By- Ananya Tiwari