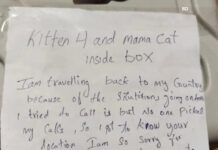

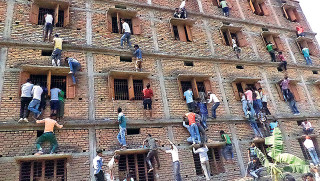

Most of us, adults and students alike, are aware of the art of knowing glances, deliberate coughing and mnemonic scribbling, all tried and tested formulas for cheating on an exam. However, last week this art literally touched new heights when the town of Hajipur in Bihar rose to infamy with the news of hundreds of parents and relatives ‘helping’ out their children during the course of their examinations. To millions across the country, the sight of a horde of people climbing pipes and sitting precariously on ledges to pass on chits to their children, while invigilators and hapless policemen looked the other way became the amusement of the week. However, as shocking, and daresay audacious the act was, the fact it happened during a State matriculation examination does little to underscore the problems that have plagued education in India. Even more shocking is the truth that such a sight is not a lone incidence, but is symptomatic of a larger issue.

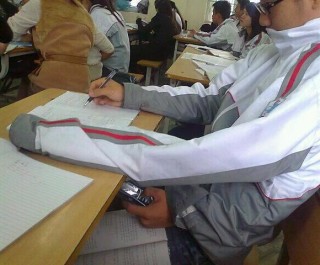

Bihar, the state of the aforementioned cheating case has a stringent anti-cheating law which in although in theory, allows jail-time for offenders but in most practical instances has done little to deter offenders, a fact best reflected by the fact that a significant number (over 200) of students had been expelled last year for cheating and their parents, relatives arrested under the same law. This month alone 600 students have been expelled and the exams season isn’t even over yet. There is also the growing number of instances where the examination papers are leaked beforehand, even in the Delhi University. Cheating too, as the cliché goes is getting monetized and becoming a business. And yet, hardly any of these instances of cheating have appeared to surprise any of us. Cheating, in other words remains a stark reality, albeit an oft-ignored one. Which is why, it is only pertinent that we answer the question, why do people cheat?

Compelled or Content to cheat?

Across most of India, examinations remain the litmus test for individual intelligence and capability. Not only has individual performance on an examination become a mode of social mobility and acceptance but of late, it has also become the best indicator of admission prospects in universities. Even the definition of a fine performance on an exam has changed over the years. Whereas 90% was the Everest of the academic world once, nothing less than a 97-98% will do today, especially in light of the cutthroat admission processes. Which is why unwittingly, the entire system of examinations has come under scrutiny for facilitating unrealistic demands for academic achievement. Often, the pressure is too much for students to handle which compels them to go forward with such drastic steps. Another common reason is one of expediency, or the easy way out. For many, cheating in an examination offers an escape route from the ignominy of being called a failure; which is why many resort to tricks like chit-making and body-scribbling for assistance during an examination.

In the aforementioned case in Bihar however, none of these reasons find conclusive validity. The closest cause that finds semblance in the happening is a sentiment echoed by the many students and parents which states that, ‘Everyone does it. It has been going on for ages’ Knowing the bad state of education in the hinterlands of this great country, there is perhaps very less doubt as to the veracity of this claim. However, as ridiculous as their justification sounds, it also reflects the State’s ineffectiveness to combat the menace of cheating across decades, which has allowed a provisional stamp to approve of this practice. Even with the anti-cheating law in force, other problems like bribery hinder the road to conducting a fair examination.

Failing in the duty to educate?

That said, it is often easy to place the blame for such a menace on the people who practice it. And to a degree yes, the blame does fall on them. But, it does not fall on them alone. Anyone who has been a student of State Education Boards will testify as to the falling quality of education, especially in the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Most such state boards remain rooted in their primitive system of education, a fact well established by the inclusion of fantastical books in state curriculum written by a certain Dinanath Batra. The fact that very few of the State boards are equipped with teaching modern-day subjects like Science and maths is also reflective of how slow their evolution has been since independence.

Another major problem is with the recruitment and qualification of teachers under the State education boards. Teaching remains sadly, a largely low-income profession in our country which means the well-qualified do not have enough incentive to try and enter this noble profession. As a result, teachers are recruited from a crop of people who are neither well-qualified to teach, nor are interested to do the same, a fact well told by the rising number of instances where teachers fail to even show up for their classes. Also, the crumbling infrastructure of public education in India has only made the problem worse, and has allowed schools to be instead used as community centers for public functions rather than the breeding ground of scientific temper (A reality well portrayed in Aravind Adiga’s ‘The White Tiger’).

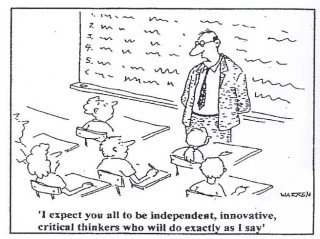

The problem with education in India also has a lot to do with purpose. In India, education is often the means to be known as a literate, or as the Census would define it, any person over the age of seven who has the ability to read, write and understand sufficiently in at least one language. That is, by no means, a wide or sufficient enough definition for a human index as important as literacy. Literacy today stands at over 70%, a marked increase in the decades since independence. However, much of it stands exaggerated because often, the ability to read, write and understand simply one’s name is enough of an indicator of literacy. If the results of a recent study which state that most fifth-graders can’t do simple maths are to believed, many of our students though literate by census standards, are not remotely functionally literate. It is this very surface literacy that has been so lackadaisically promoted by a majority of the State and government-run schools across the country, where rote learning is given preference over actual knowledge.

The motion of whether ‘The British Empire did more harm to India than good,’ was held in the affirmative at a recent debate in London. However, against the tide of debate many, even the critics of the British Empire agreed upon the quality of the modern-day education system, a relic of the British era, which is why some of India’s best schools, even today remain those established during the colonial age. That said, it must be noted that it is perhaps given that the ‘quality’ those fine gentlemen talked of was said of the schools and institutions under the CBSE, ICSE and IB. State-run schools feature nowhere in that scale of quality education, and rightfully, they shouldn’t. State boards remain, like a lot of the land in India, a lawless, almost anarchical state of affairs. But, considering the progress made by its sister educational boards such as those aforementioned above, it remains possible to elevate State-run educational boards to one of respect and dignity, something it needs to achieve considering the millions of students under its shadow.

Mandela once said that education is the best weapon to change the world. However true that is, it can never be powerful as long as it remains unsharpened by the attitudes of the students, teachers, parents and the education boards across the country. A progressive change must be made, not only in normative action against the menace of cheating but also, in our attitudes towards the purpose of education. If not however, the nation can always thank the smart Alec who came up with the phrase, ‘Cheating requires brains as well,’ as another tower of shame creeps up the crumbling red bricks of an examination hall.