The Business Solution to Poverty: Designing Products and Services for Three Billion New Customers. By Paul Polak and Mal Warwick. Berrett-Koehler; 264 pages; $27.95. Buy from Amazon.com

ONE of Paul Polak’s first innovations for the poor, back in the early 1980s, was to re-engineer donkey carts for refugees in Somalia, a project he and his colleagues jokingly named Ass Haul International. Their carts, which were more flexible for users and more comfortable for the donkey, cost around $450 and could generate revenues of $200 a month. The increased steady income that the new carts gave those who bought them offered Mr Polak his first proof that innovation and business can be a powerful tool for getting people out of poverty.

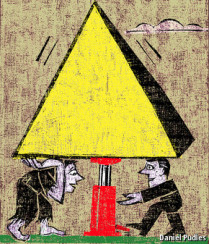

Although it was a heretical thought when Mr Polak started out, today the idea that business is better able to help lift millions of people out of poverty than international aid or charity borders on conventional wisdom. Connecting China’s poor to the businesses of the global economy reduced by at least half the number of people living in extreme poverty, less than $1.25 a day, and enabled the world to achieve the Millennium Development Goal ahead of time. Less than a decade ago, the priority of policymakers was to get more aid for Africa; now they promote investing in African businesses, pointing out that the continent now boasts some of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

In this new world aid and charity are criticised for seeing the poor as victims in need of handouts, which help breed dependency. Business, by contrast, treats poor people as workers and customers, empowering them to stand on their own feet. The crucial role that markets and companies can play in economic development has been ignored too often in the past, so Mr Polak’s focus on business solutions is welcome, even if he compares them too starkly against the weaknesses of aid. Both have a role to play: for all the ingenuity of drugs companies, for example, recent progress in vaccinating millions of people in poor countries would not have happened without billions of dollars from foreign governments and philanthropists.

This is at once inspiring and a bit daunting. A chapter on an unsuccessful effort to create a business making charcoal out of agricultural waste in Haiti is a reminder that great talent and good intentions are no guarantee of success and that, as the authors say, “markets can be merciless”, especially when the customer is poor.

Hence their emphasis on spending a lot of time talking to poor customers as part of “zero-based design”, creating products with the “radical affordability” to appeal to people earning only a couple of dollars a day. (Mr Polak co-founded a non-profit organisation called D-Rev that does just this.) In order to become cost-effective these products need to be sold on a large scale, which means designing and building businesses that are capable of reaching at least 100m customers. Mr Polak, a psychiatrist turned social entrepreneur, has experience of this. Two of his start-ups, Windhorse International and Spring Health in India, are aiming to do precisely that with products such as safe drinking water, bio fuels and rural education.

But if your business idea looks like it might fit the bill, this book may be just the guide you need to help you on your way.

Credits to : The Economist Oct 12th 2013 |From the print edition Oct 12th 2013